FOUNDERS KEEPERS: The Bottle Rockets and The Legacy of Misfits Piecing Together a Living

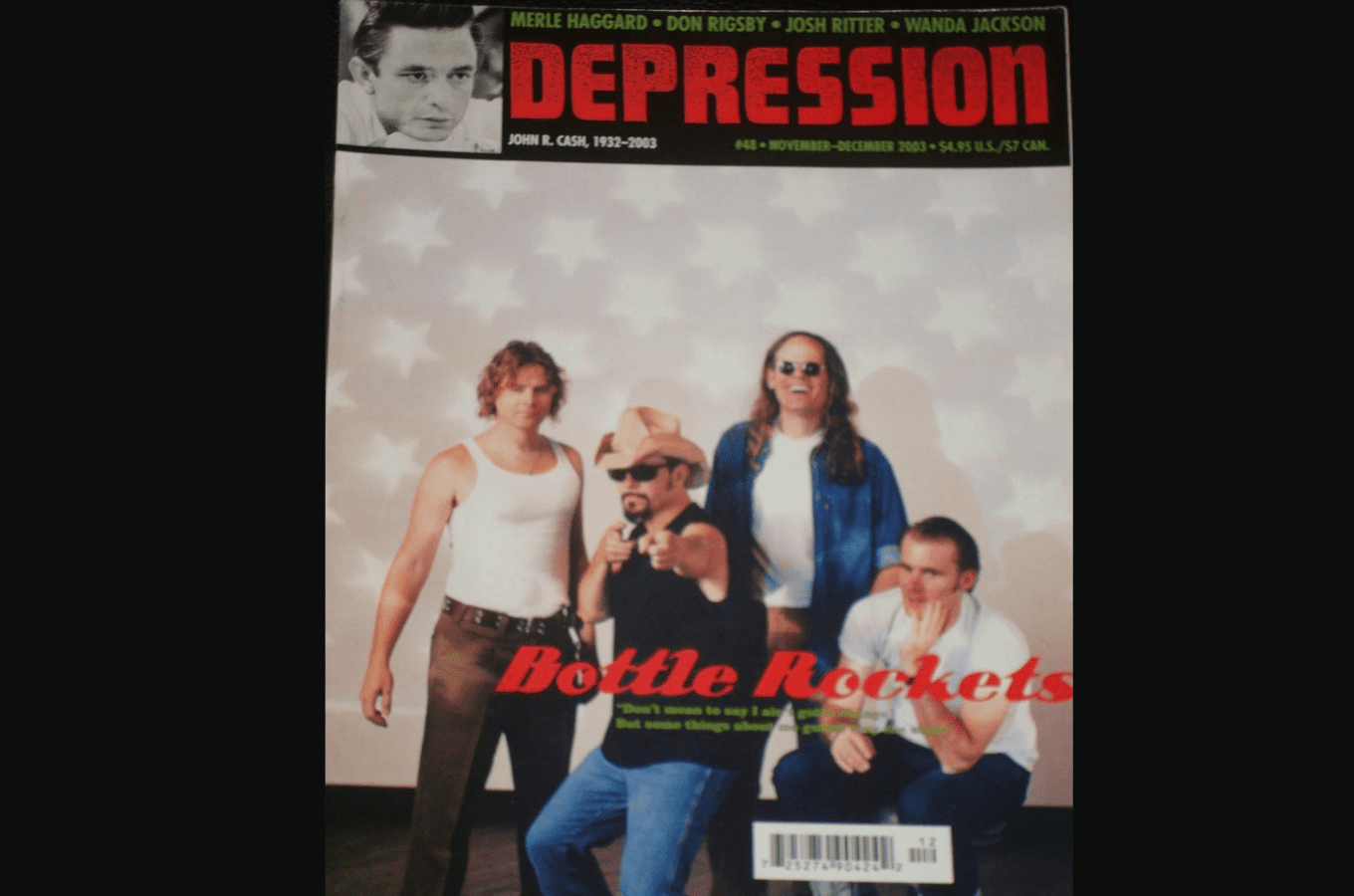

The Bottle Rockets on the cover of No Depression from November-December 2003

This is going to be about The Bottle Rockets, the other alt-country band from St. Louis, that graced the cover of the original magazine twice (even though the second time we all knew the futility of the gesture).

But it’s going to take a while to get there. Because first we have to talk about clothes.

I come from grunge. Flannel is not a costume. It’s what we wore — what I still wear — because it was cheap and it stayed warm when damp, and it lasted. Same with jeans and Doc Martens, though Docs never quite fit my feet. I have never owned a tie. I have never had a proper job interview. I have never worked for a company with more than 50 employees, unless we really have to count when I went door to door for the Fuller Brush Company in the summer of 1977. Clothes make the man, right?

“There’s a race of men that don’t fit in…” — Robert Service

The Spell of the Yukon was my first “little red book.” I suppose Robert Service wrote doggerel (“The Cremation of Sam McGee,” et. al) and he wrote in the people’s key. Those are my people, the ones who don’t fit in.

I ended up with two copies of The Spell of the Yukon, one from each grandfather. When it came time to fly to Austin to interview Billy Joe Shaver, tender days after he had buried his son and collaborator, Eddie Shaver, I packed the extra copy and put it in his hard-worn hand. It fit, and that’s all I’m going to say.

Now go listen to “Blood is Thicker Than Water,” and imagine those two hard, proud, difficult men working together to craft that song — their last and perhaps greatest work — from the literal truth of their lived and shared experience. Billy Joe calls his son’s gal “the devil’s daughter,” and Eddie answers in kind: “I’ve seen you puking out your guts/and runnin’ with sluts/when you was married to my mother.”

“Blood is thicker than water.” They sing that part together, and the art they made together was stronger than all of it.

“Four in the morning/And the water is pourin’ down…”— Jesse Colin Young, The Youngbloods

Have we need, in this moment, to speak of our old friend the blues, to acknowledge the black dog who shares our bed and drinks our coffee and stares back from the depths of the mirror? Perhaps not.

So we started this damned alt-country magazine, because god, what happened to punk rock?

We were “going to where there’s no depression,” or trying to, cobbling together some new kind of virtual peace and community which sought to give voice to our rage and our joy and our hope, and for those few moments, listening, we were not alone.

(Well. That was my urge, my need, my urgency. Peter Blackstock is a better-adjusted fellow, I think.)

The Jitters were very first band I ever interviewed, led by a guy named P. K. Dwyer. He and his singing partner, Donna Beck, had been buskers, had made a living playing 20-minute breaks between sets and passing the hat. The Jitters was his attempt to go commercial. They made one record in 1980. It’s proto alt-country. Jason and The Scorchers should’ve covered “You Say You Love Me But You Won’t Do Anything About It.” Or maybe Robbie Fulks. Dwyer came by my apartment to be interviewed, flipped through my paltry record collection until he came to a Sonics LP, and somehow that led to him blowing his voice out during an encore singing “The Witch,” opening for Pearl Harbour & The Explosions at the old wretched Showbox.

I said this a lot because we were asked the question a lot: Punk rock and country music (the old stuff, say Hank Williams and Loretta Lynn) don’t require technical virtuosity. Enjoy the anarchic stray beats of Willie Nelson’s cowboy measures and embrace the glorious imperfection of the human voice (and I’m not going to pick on Willie a second time). Both also depend utterly on the performer’s ability to hold onto the absolute truth of a song, even while singing it every night for the rest of their lives.

So “alt-country” was a phrase I heard from an old friend named Bev, who had worked for A&M during Soundgarden’s rise, and at the time was working for 4AD and managing a San Francisco band called Tarnation.

Peter, my endlessly patient co-founder, would consider no name but No Depression. Fine. Perfect, in fact: My seven-year relationship was ending. My art gallery was clearly going to fail. My writing career wasn’t a career because I have the freelance instincts of roadkill, otherwise I’d have been good at the whole Fuller Brush thing. And my dog was dying. Good dog, big old red Chow Chow, scared of storms, 90 pounds on my chest in the middle of the night. So, sure. No Depression.

Oh, the ugly truth? I never really listened to Uncle Tupelo. But that first Son Volt album, the one we launched a magazine behind? Still holds up.

We started No Depression in Seattle while grunge was still all the rage. Seattle was home to a well-honed appetite for irony, one of the reasons grunge worked there, and played so differently elsewhere. So we started a magazine about some form (or forms) of country music while living in the epicenter of an alt-rock scene — the last one, as it turned out. It became alt-country, simple as that. Peter’s late father explained the rest to a friend, and it stuck: “Whatever that is.”

“Overworked, Overloaded, Underpaid” — The Picketts

A lot of white male stuff going on here. I almost missed Christy McWilson, first in The Picketts (who had two albums on Rounder), and then on her own, sometimes aided by Dave Alvin and his crew. She lived in the shadow of Seattle legend Scott McCaughey, he of The Young Fresh Fellows, R.E.M., and some other stuff.

Christy was right in my backyard while I was busy awkwardly bopping in front of the soundboard, being buffeted by righteous male angst. But if you go back, if you want to hear powerful, brilliant, furious feminist alt-country, it’s right here in “Good Good Wife,” “Little Red Hen,” and “Tightrope.” If it didn’t come to more, well, they had a daughter and he had a career, right?

Same as it ever was.

Christy also covered The Youngbloods’ “Darkness, Darkness,” which I mention because it’s a terrific version and, y’know, “No Depression.”

Here’s the thing: I don’t give two shakes of a rat’s tail about money. I don’t care how many units get shifted, how many spins you get online, how many years you spent perfecting your craft. Give me artists who press on, regardless the vagaries of commerce. Billy Joe Shaver used to say he’d tried to quit plenty of times, but there was no place to turn in retirement papers. He couldn’t stop. The good ones can’t. Those are the ones I still listen to, the art I still care about.

This makes me an unsuccessful former music critic. The game, of course, is to attach yourself to a career on the rise and ride the celebrity elevator ever after. That’s what happened to punk rock and to country music.

I went to a community meeting in Nashville when Napster was a thing and MP3 files were just rumors. Older guy with ironed creases in his jeans stood up, said, “Used to be we’d buy a bottle to celebrate if a single sold 40,000 copies. Now we buy a bottle to commiserate.”

What P. K. Dwyer said in my first college apartment was that he wanted a career like Elvin Bishop. Just the one hit song, “Fooled Around and Fell In Love,” right? But Elvin Bishop could tour anywhere he wanted, play everything he felt that night so long as he encored with the hit, be assured of a decent crowd and a tolerable payout when it was over.

That’s a life. That’s the life, if you’re about the work. Or at least it was.

So The Bottle Rockets, where this started. They quit a few years back. I get it. Hell, so did I. At their best, they were angry and funny and fully committed. Go back and listen to “Welfare Music,” first track from their debut. Or “1000 Dollar Car,” man did I live that in my 20s. Or “Kerosene,” with the phrase “If kerosene works/why not gasoline.” It’s about a trailer burning down when someone put the wrong fuel in the heater because they’re broke.

I love those songs. I miss those songs. They weren’t pretending, not a bit, and certainly not pretending to be something they weren’t.

So here’s the thing I’m dancing about, the thing we so rarely talk about — class. Robert Service wrote simple, straightforward verse for working folk, or that’s how it landed for me. Same with Billy Joe Shaver and Christy McWilson and The Bottle Rockets and pretty much all the artists I still listen to. I’ll take Merle Haggard over Bob Dylan every single time. I still think country music changed because the executives were ashamed of their audience.

Once upon a time, we committed to the proposition that we could write about and honor and celebrate music because we liked it, not because it could be sold. Oh, we hoped it could be sold. Every damn business I’ve ever been a part of had as its core principle the hope to help other misfits piece together a living, so that nobody I knew ever had to wear a damn tie unless they wanted to. So I wanted them to have what Elvin Bishop had, what Mudhoney has held onto.

What matters. Hang on to that. The music matters. And if it stops mattering we’re all [insert dirty word here].

“…beware of all enterprises that require new clothes, and not rather a new wearer of clothes.” — Henry David Thoreau, Walden.

I was barely 11 years old when I read Walden the first time. For decades I only remembered the first half of that sentence, but old Henry David was at least a fringe transcendentalist. And I’m still wearing the same old clothes.

Go listen to some good music and always tip your barista.