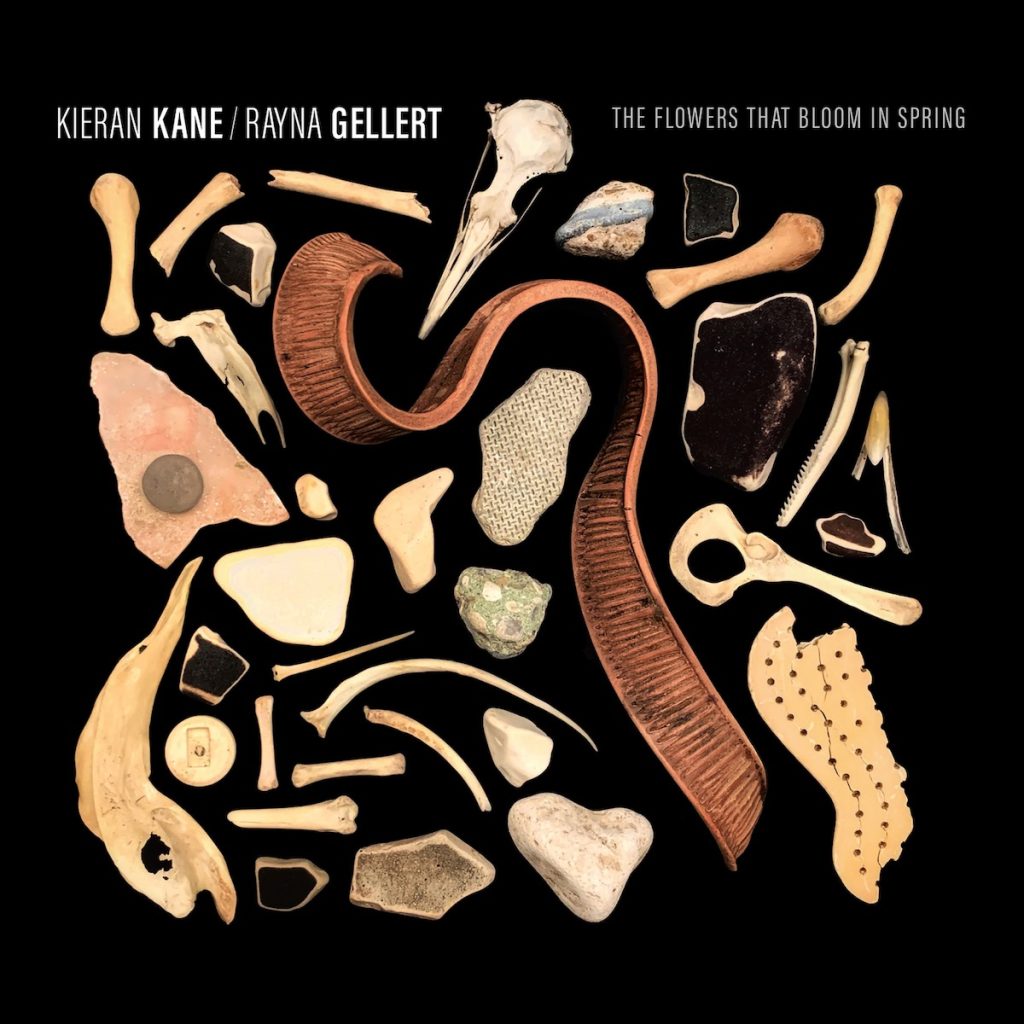

ALBUM REVIEW: Kieran Kane and Rayna Gellert Renew Magic on ‘The Flowers That Bloom in Spring’

To duet well is to dance, to step in rhythm in such a way that the two become new and unified; two streams merged into a river, if you will. Kieran Kane and Rayna Gellert dance so closely on their new album, The Flowers That Bloom in Spring, their voices may as well have been forever joined.

Both individually accomplished in their own rights — Kane for shaping country music and Americana as part of The O’Kanes and creating the label Dead Reckoning, and Gellert for her accomplishments as one of the world’s greatest old-time fiddlers — they combined forces yet again for this new album. It is their fifth collaboration since meeting in 2017 at the Hardly Strictly Bluegrass Festival. First they supported each other’s solo albums, but The Flowers That Bloom in Spring represents their third album written together (following The Ledges and When the Sun Goes Down).

Kane and Gellert holed up in a house on an Adirondack lake, in part to record music for Martin Scorsese’s upcoming film Killers of the Flower Moon, and the creativity flowed. They settled into a rhythm, and out came The Flowers That Bloom. They co-wrote seven songs, adding one solo credit each, and fleshed out the album with two tunes pulled from the American songbook that matched the mood and feel of the record.

Steady guitar grooves and fiddle melodies ground each song, lending them a timelessness. These songs feel old and undiscovered, little gems mined by Kane and Gellert. They explore themes familiar to fans of the greater folk music world — surviving hard times, unsettled hearts, love, and redemption — but it is the instrumentation twined with the harmonies that defines The Flowers That Bloom in Spring.

Gellert’s fiddling deepens songs, such as on “Lonely Are the Brave,” on which her opening instrumental carries a true sense of mourning. Throughout, her playing stretches the emotion into something almost tangible, and it becomes easy to feel along with the song’s narrator. This contrasts neatly with a song like “Augustus,” wherein Gellert’s voice is the star over softly plucked strings, combining to suffuse the song with memory and regret.

Gellert and Kane selected a particularly choice duo of covers, though the beauty of “Please Help Me, I’m Falling” is especially revelatory. Mostly true to the melodies of the original (first recorded by Hank Locklin), they slow it down, tangle their voices tightly together, and gift the listener kind of love song that feels sweet, but not saccharine.

The album’s standout, however, is the cautiously hopeful and haunting title track. Harmonies — vocal and musical — story the songs, rendering them almost as late-night kitchen table talks. Gellert fiddles sprightly, and Kane sings each verse softly and sweetly. His voice carries the song near to its ending, singing by himself until Gellert suddenly joins for the last few lines. It is a rapturous moment, a last unveiling of beauty and closeness before they play a final instrumental sequence. As the quiet of an ended record settles into place, their harmonies haunt, little ghosts that keep playing through the silence.