SPOTLIGHT: Charley Crockett Builds His Own ‘Music City USA’

Photo by Bobby Cochran

EDITOR’S NOTE: Charley Crockett is No Depression’s Spotlight artist for September. Look for more about him and his new album, Music City USA (out Sept. 17), all month long.

In a scene from Peter Bogdanovich’s 1993 film The Thing Called Love, two young Nashville hopefuls shout into the night from a downtown rooftop, “Look out Music City, ’cause I’m here now and I ain’t never leavin’!” It’s a rite of passage for singer-songwriters, one explains to the other, when you come to Nashville, the epicenter of the country music business. But to Charley Crockett, his new record Music City USA has everything and nothing to do with the infamous Tennessee hub. “Music City USA to me is any street corner where I put the damn guitar case down to make money,” he says. “I came into my own as an itinerant performer.”

Crockett’s story has been well documented: He came of age as a street performer — busking in New Orleans, New York City, Paris — wherever the road took him. He had a brush with a major label, run-ins with the law, and stints as a farmer in the Pacific Northwest. By the time he entered his 30s, several records poured out of him in quick succession. But last summer’s Welcome to Hard Times hit different. Crockett’s instinct to release it amid the pandemic was a good one. Had it come out this year, it might easily have been buried under the countless 2020 holdouts that seem to drop every week. Instead, it sold like wildfire and garnered him a bigger, younger audience and plenty of exposure, even without a proper tour to back it up.

But Welcome to Hard Times didn’t stand out only because it had less competition. Its themes — hell, its title alone — spoke to the strife of 2020. “I wrote that record before all the shit hit the fan. It was personal. I was writing from my own personal trials with heart surgery and dealing with the commercial music business,” he says, referring to the life-saving heart valve replacement surgery he underwent in early 2019. “That’s the thing about art, is the artist can impact the times, but there’s another aspect to it that’s far more mystical, which is the times themselves is what will choose what makes an artist relevant. And that’s absolutely what happened with that record.”

It was also borne out of a long road toward establishing himself as an artist on his own terms, and it was a good lesson in staying the course. “What matters to me is that I have a grassroots audience,” he says, “And I know that if the records are good … I get to continue to have the unbelievable privilege of putting out records whenever I want with nobody standing in my way telling me how they should sound.”

What Crockett possesses isn’t cynicism about the music business, it’s savvy. He’s faced his share of rejection, people not understanding him or his music, and the struggle to fit in somewhere. “Being 37 and playing music from a street corner at 17 to now, a lot of the people knocking on my door recently, there’s not a lot they can do for me,” he says. “I know that major label system and let me tell you what happens: A lot of people end up disillusioned and they might be lucky to get three records out, get their ass handed to ’em, have a hard time being in touch with themselves, get taken advantage of, and then are completely out of the business because of how mistreated they were. And that’s a damn shame because when you’re 60 years old what do you have to look back on?”

In the Alleys

Music City USA, Crockett’s tenth album, is a double LP written in a month and recorded even quicker. Its songs tell stories of self-preservation and determination in Crockett’s signature twangy, velvet croon; of finding your own path, however unconventional — something Crockett has mastered. Despite what the upbeat fiddle and steel guitar arrangements may suggest, the lyrics are dark threads woven into gritty tales of survival, sung in that rich, sometimes baritone voice of his. He’s on the run looking to escape (“Honest Fight”), weary of the state of things (“The World Just Broke My Heart”), and just trying to be seen and understood (“Smoky”).

All the while, Crockett subverts the country-western genre, fusing it with blues and rock and roll in a way that feels wholly him. “I Need Your Love,” “I Won’t Cry,” and “This Foolish Game” are sultry R&B tunes that showcase Crockett’s undeniably natural swagger. He likens it to the sounds of some of his heroes.

“‘Country’ is really just such a broad term. You can almost replace ‘country’ with ‘American’ or ‘blues’ or ‘soul’ or any of those things. They’re all borrowing from each other,” he says. “In my opinion, a lot of what’s called country is not any good and it doesn’t sound anything like the great country music that everybody claims to be motivated by. … Because if you’re listening to Waylon Jennings or George Jones … especially in the ’60s … that shit is very eclectic.”

Crockett’s self-described “backdoor relationship” with Nashville is best described in the lyrics of a new song he’s been working on for a future album:

They laughed at me in New York City

Called me a fool in LA

I doubt that Nashville saw me comin’

Besides the bar folks workin’ late

In those early days, he’d hobo through the city, sometimes staying at the storied Drake Motel, often playing to sparse crowds. He found solace in the supportive bartenders who’ve seen it all but would still ask for CDs after his shows, and in the empty alleyways behind venues. Music City USA’s title track alludes to this: “There underneath the lights of Broadway / I’m in the alley with the ghosts.”

It isn’t just about Nashville, he explains. “I found that to be true in New Orleans, San Francisco, New York City … the greats of the earlier era, I feel those people’s spirits in the alleys. … That’s just how I feel about a lot of America in general, is being in contact with the ghosts because they’re there.”

Crockett connects with those ghosts in all kinds of ways, but maybe none more strongly than the comparisons he gets to artists like Jones and Jennings. The question of authenticity comes up a lot when it comes to Charley Crockett. Perhaps it’s the distinct aesthetic choices, the cowboy hat and boots. Or maybe it’s that low, Southern drawl that seems to echo from some past era.

“People consider Hank Williams to be the most authentic country singer ever to be around,” Crockett says. “But Hank Williams never wore a cowboy hat in his life until he started singing country music. Hank Williams was singing showtunes.” Crockett isn’t a persona, he just loves to put on a show, not concerning himself with how much people might read into it.

“I’ve done all the shit that I’ve ever claimed that I’ve done,” he says. “What I’ve learned how to do is tell the story. Why I love country music — however all of the ways people project and judge my version of country and all of the things people claim that I am and that I’m not — is the storytelling aspect.” The fugitive tune “Muddy Water” is an example of the way Crockett, as he puts it, “pours [his] life experience” into the stories he tells. “Is that my exact story? Did I go to jail in Nashville and I got hounds on my trail crossing back into Georgia from Tennessee?

“No,” he states. “That happened to me in Virginia.”

Timely and Timeless

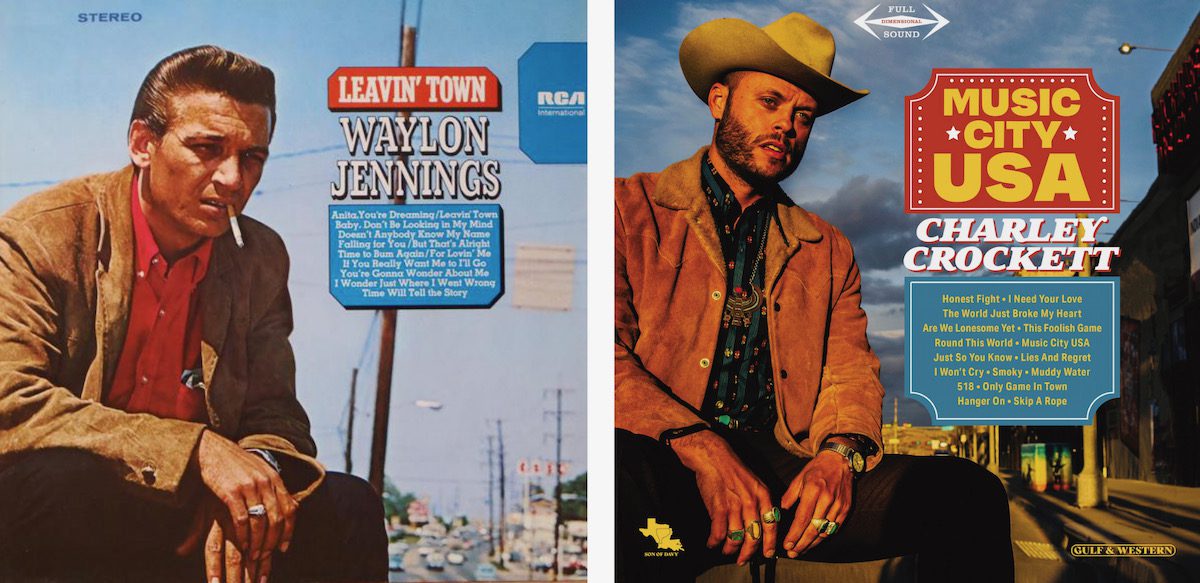

When creating the album cover for the new record, Crockett was inspired by the image on the cover of Jennings’ Leavin’ Town, in which he sits right square in the middle of one of Nashville’s major boulevards, a cigarette dangling from his lips. But in true Crockett fashion, he wanted to give it a twist.

“I thought, man I’d really like to do something like that, but … what’s the opposite of Music City USA? Well, there’s a town in New Mexico on the 40 and its nickname is ‘The Most Patriotic Town in America,’” Crockett says, referring to a title bestowed by map and atlas publisher Rand McNally on Gallup, New Mexico, where he shot the cover for Music City USA. “And here’s the irony in that: That’s the most Native American town in America. … Gallup is considered the center of the Native world, it’s in the middle of Navajo country — Zuni, Ohkey, that’s all Native. So I’m sitting on a chair in downtown Gallup. Maybe that’s Music City USA, the center of the Native world. That was on purpose. I don’t even know what the hell it means, but it’s damn sure ironic.”

No matter what, Crockett stays true to himself, the person that’s been through real hardship, hustled to get where he is, and lived to tell the tale. And he has no intention of slowing down: He’s already completed two albums’ worth of new songs since making Music City USA. “At [my age], sure I’ve been around a while, but I do think I’m just beginning to have an idea of how to really write songs,” he says.

“The question that you could present to … any kind of analyzing artist is, ‘Is there anything that you’re doing that could be considered timeless?’ And we don’t even have to answer the question because in 20 or 30 years, America will decide, another generation will decide. They called me a stylistic chameleon in Austin and initially it pissed me off, but now I’m just like, fuck it, I’m a chameleon. Like George Jones, when they first started calling him ‘The Possum’ he hated it, then he started putting it on T-shirts.”