THE READING ROOM: Richard Thompson Reflects on Fairport Convention, Songwriting, and More

The best music memoirs simply unfold the moments of an artist’s life, without fanfare and without a desire to get even with former bandmates or friends. The best memoirs reveal to us — and revel in — what the Romantic poet William Wordsworth called “spots of time,” those moments that stand out in our lives when we cast our glances back and that often define us.

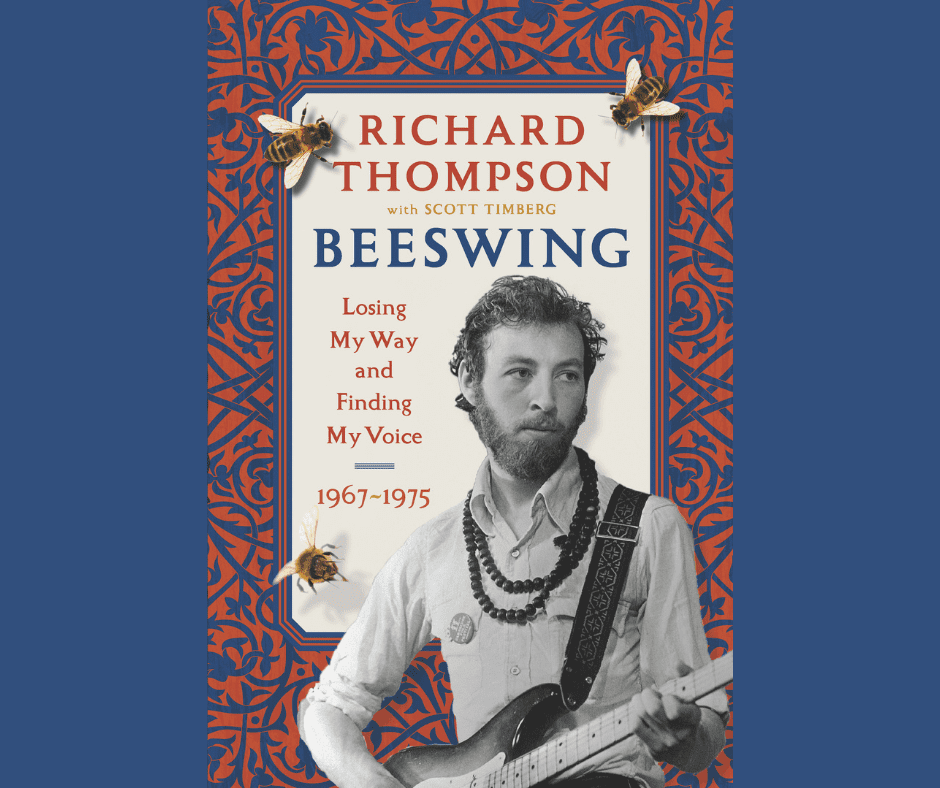

Richard Thompson is no Romantic, though there are likely fans of Fairport Convention, the band that he helped form in the late 1960s, that would cast themselves as Romantics, looking to return to an idyllic and pastoral nature far from the dust of the city. Nevertheless, Thompson’s inviting new memoir, Beeswing: Losing My Way and Finding My Voice, 1967-1975 (Algonquin), offers us glimpses of spots of time during which Thompson discovers his passion for playing guitar and for writing and playing music and reflects on the years at the beginning of his career that shaped him and his outlook on music and, in some ways, life.

The opening chapter of Beeswing starts appropriately enough with an epigraph from John Cage: “I have nothing to say, I am saying it, and that is poetry as I need it.” Cage’s caginess conveys Thompson’s own tentativeness in offering up these reflections of these eight years when he moved from his early band days to the halcyon days of Fairport Convention to living in a rural community with his wife, Linda, and their children, raising chickens and growing vegetables. In his opening paragraph, Thompson wonders about the value of looking back, and also wonders whether he’ll be able to see through the fog of time to offer clear visions of the past. “This remotest room of my mind has been shut up for years, the windows shuttered, the furniture covered with dust sheets. Light hasn’t penetrated into some of these corners for years; in some cases it never has. If something is uncomfortable, I shove it in here and forget about it. When was the last time I dared look? I don’t want to remember, but now it is time to think back. The arrow is arcing through the air and speeding towards its appointed target.”

In the spring of 1967, Thompson has just turned 18, and he’s finishing up school and has no desire to be cooped up in university or in a day-to-day job in any kind of institution. He has only one desire: “I only cared about the guitar.” When he was 11, his father brought home a damaged guitar and fixed it. Even though his father had ideas that he’d play the guitar and his sister “had designs on it,” Thompson “had other ideas. It was as if this sacred object was being pulled towards me by a giant magnet. This was my destiny, and no one else stood a chance.” Someone loaned him a guitar instruction manual, and soon enough he was taking some lessons and playing with some friends. At 18, he recalls, his path was, in many ways, set: “So much of my pleasure and self-esteem came from music and art, and I longed for a life where I could devote more time to them. I considered myself a reasonable electric guitarist — I wasn’t very original but I had quite a range of influences, and I longed to play more music. … I believed in a more abstract version of a benign universe; I thought everything would turn out fine.”

In its early days, Thompson reflects, Fairport Convention “seemed to be swept along by the fates, with possibilities opening up where we turned.” When Sandy Denny joins the band in 1968 as the lead singer, the band sounds “a lot more accomplished and musically complete. The voice at the front of a band is a vital focus, carrying all of a song’s emotion, and if that voice is as strong and intriguing as Sandy’s, with such an ability to tell a story, it just lifts everything else.” As Fairport Convention begins to grow, so does the band’s conversations about the songs they’re writing and the folk songs they’re selecting for their set. “The singer is less important than the song. We were starting to connect to a lineage that was ancient, pagan and alive with the dreams of the dead.”

As much as this is Thompson’s story of his days in Fairport Convention, though, it’s also a chance for him to reflect on songwriting and the power of music. Thompson and the band part ways in 1971, and he eventually moves to Suffolk, where he lives with his then-wife and musical partner Linda in a “thatched cottage of some antiquity near the village of Hoxne, at the end of a long, winding lane.” That life eventually shifts too, and he returns to London, and while there are fallow periods in his songwriting, he uses his own experience of writing the song “Beeswing” in 1994, 20 years later, to reflect on songwriting. “I think we write songs for pleasure, but also to understand ourselves and to decode life. I have written songs about the Second World War in an attempt to understand my parents’ generation and what they went through. … I’m also always trying to figure out why I am the way I am, and the forces that brought me to this point. ‘Beeswing’ reflects upon a generation of dropouts, willing dropouts, and the likes of Ted [a tramp who stopped by Thompson’s house every four or five months looking for manual work in exchange for food or money].”

Beeswing sparkles with luminescence, illuminating not only Thompson’s journey but also shining moments in the British music scene that we too often forget.