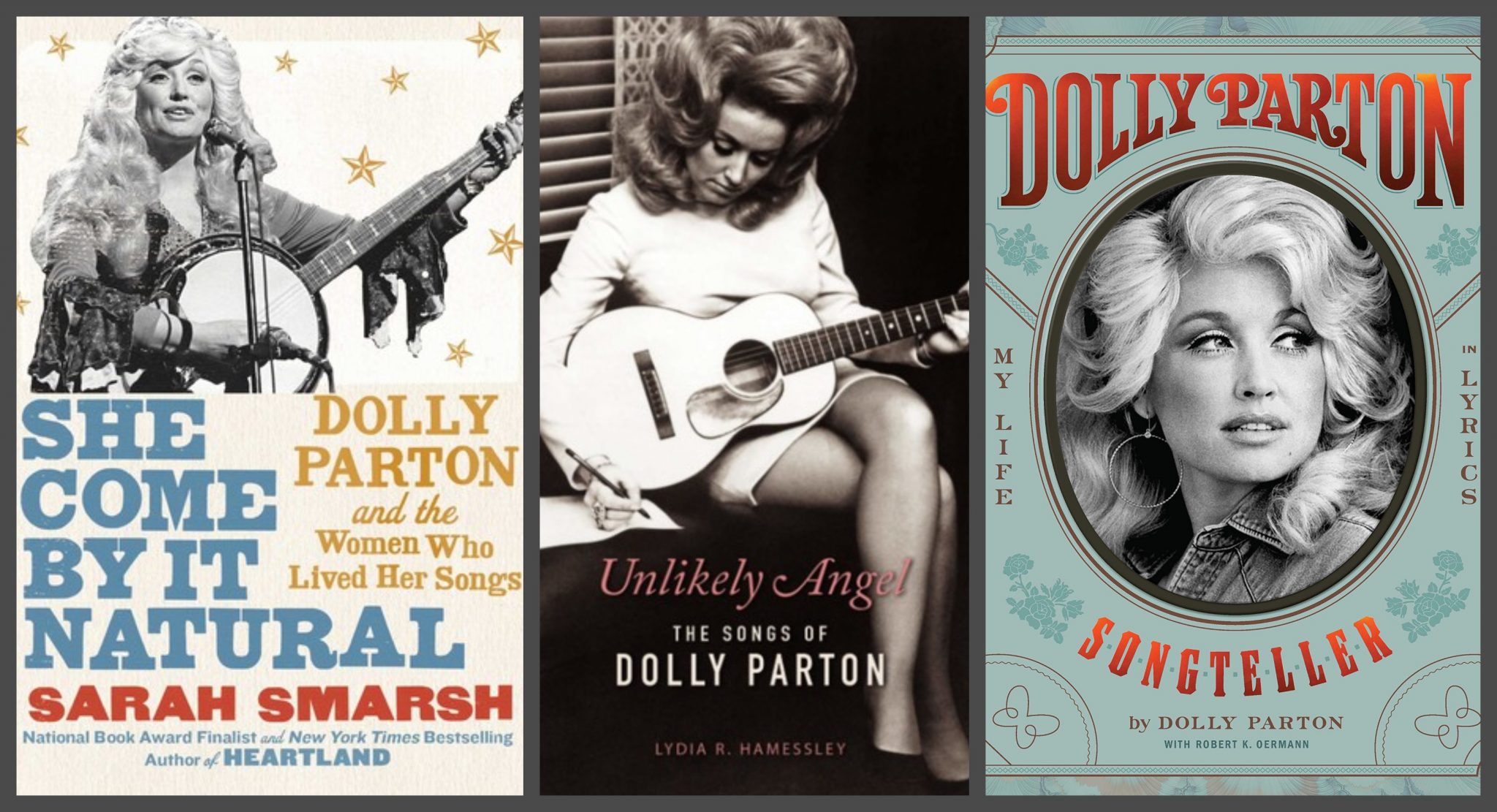

THE READING ROOM: Three New Books About the Life and Songs of Dolly Parton

’Tis the season to love Dolly! In October, Dolly Parton released A Holly Dolly Christmas, an album of Christmas favorites that includes duets with, among others, Miley Cyrus, Jimmy Fallon, Michel Bublé, and Willie Nelson. And Parton has recently been in the news for her financial support of the development of a COVID-19 vaccine. In addition, three new books — two about Dolly and one written by Dolly — each focusing on different aspects of her life in music, are now available.

Sarah Smarsh’s She Come by It Natural: Dolly Parton and the Women Who Lived Her Songs (Scribner) first appeared in serial form in No Depression’s print journals in 2017. Part memoir, part cultural history, and part music journalism, the book traces Parton from her hardscrabble life of poverty in east Tennessee as the fourth of 12 siblings to her leaving home for Nashville at 18 and slowly making a name for herself as a backup singer to her days with Porter Wagoner, her film roles, the opening of Dollywood in 1986, and, of course, her music. As Smarsh, who grew up in transient poverty in Kansas in the ’80s and ’90s, points out, girls like her were watching Parton and the ways she had driven away from poverty and achieved fame and created a dazzling career that she had full charge of.

“She was entering the apex of her career — a period in which she would become not just a movie star but a business magnate and global icon. She would do it all sporting a huge platinum-blond wig, skin-tight clothes, and ample cleavage. She was, perhaps, a third-wave feminist born a generation early, simultaneously defying gender norms and reveling in gender performance before that was a political act. Country girls like me — in places feminist polemics don’t tend to reach — were watching.”

Smarsh’s Parton is not only a country and bluegrass music icon, she’s also a creative and brilliant entrepreneur always on the lookout for new projects that improve the world and give back to her own mountain region of it. “Parton’s rural upbringing, as well as the talent that set her apart from other kids, meant that her closest friend was the Earth itself. It’s easy to believe that an icon known for her groundedness has been re-creating that experience on a trail through her Tennessee compound.”

“Whatever sort of icon she is,” Smarsh writes, “whatever she represents to her fans and the rest of society — a wax sculpture wearing sequined shoulder pads in a Los Angeles museum of celebrity likenesses, a barefoot bronze in East Tennessee, or a living national treasure who defies easy categories — Parton survived and even changed a man’s world so brilliantly that one occasionally sees on T-shirts or online memes an unlikely reference to perhaps the most powerful, least political feminist in the world. It’s a line that, Parton recalled on Kimmel, her own father had on a bumper sticker on his pickup: “Dolly Parton for president.”

While Smarsh offers a brilliant cultural commentary on Parton, musicologist Lydia R. Hamessley provides a dazzling close reading of Parton’s songs and identity as a songwriter in Unlikely Angel: The Songs of Dolly Parton (Illinois). Drawing on interviews with Parton as well as on deep archival research, Hamessley illustrates how Parton’s songs echo facets of her life in chapters that focus, for example, on “Dolly’s Appalachian Musical Heritage,” “Dolly’s Mountain Identity and Voice,” “Songs about Love,” and “Songs about Women’s Lives.” Rather than approaching Parton’s life and music chronologically, Hamessley demonstrates “how intertwined her music is by encountering and reencountering Dolly’s melodies, lyrics, and ideas in a variety of contexts as different stories and elements of the same song emerge — and families of tunes and lyrics materialize. Dolly is gifted at transforming specific feelings and circumstances into songs that lend themselves to multiple readings.”

As Hamessley points out, “Dolly has a core set of values that guides her life and informs her songwriting, and these beliefs are genuine regardless of how she fashions her appearance. I start with the premise that Dolly’s songs are the primary way she expresses her core beliefs, and my analyses reveal the resonances between Dolly’s songs and her ideas. Her songs illuminate what she is most moved by. They reveal what she values in relationships, what she thinks about situations and systems of injustice, and the nature of her spiritual life as expressed in both sacred and secular realms.”

Hamessley concludes by pointing to the way that music has been the center of Parton’s life and the way it lives in her soul and ours. “Early in her career, Dolly wrote a song about music itself, ‘There’ll Always Be Music.’ Although not well known, it is a statement of what she holds most dear about music as a boundless and abiding presence in our lives. Incorporating the modal sounds of her Appalachian heritage, Dolly fuses her reverence for nature with music: the wind whistles and sings tunes while rain beats out rhythms and birds join in song. The song’s chorus encapsulates Dolly’s affinity for story songs, her propensity to link music with the divine, and her belief that music will last long after we pass away: ‘There’ll always be music as long as there’s a story to be told / There’ll always be music ’cause music is the voice of the soul.’”

Parton tells her story in her own words through her songs in Dolly Parton, Songteller: My Life in Lyrics (Chronicle), written with Robert K. Oermann. As she says in the book’s opening pages, “I write a lot from my own heart. But I also just have a big imagination. When I was young, we didn’t go to the movies, so I just created my own stories. It’s kind of embedded in me to make up songs and stories.” A gorgeous book filled with never-before-seen-photographs and memorabilia from Parton’s archives, each chapter focuses on some portion of her life, from growing up (“My Tennessee Mountain Home”) and her early days in Nashville (“Down on Music Row”) to her early movies (“Working 9 to 5”) and her bluegrass albums (“The Grass is Blue”).

She provides the complete lyrics from 175 of her over 3,000 songs, and tells the story of each songs and the way it illustrates the part of life in which she wrote it. For example, she writes of “The Bargain Store”: “When I wrote ‘The Bargain Store,’ I swear on my life that I was never thinking about love in any vulgar way. I was using the ‘bargain’ as it related to a broken relationship. But every man I know thinks it’s dirty. Somehow, this lyric is a dirty thing to a man. But I never saw it that way. All I was thinking of was the heart: ‘If you don’t mind the merchandise is slightly used, with a little mending it can be good as new.’ I was saying that you’ll be surprised at how good this broken heart is. Just take it. You’ll never be sorry that you did. Just come inside, come inside my heart. The words just meant that I’ve had relationships: I’ve been through stuff; I’m not new at this. I thought for sure that I had written a hit song. And then the disc jockeys wouldn’t play it, because they thought it was suggestive. At that time, they were so difficult. Now you can show something much stronger on TV, and people don’t think a thing about it.” Reading Dolly Parton, Songteller: My Life in Lyrics is almost as good as listening to one of Parton’s albums.

There’s something for everyone in each of these books. If Dolly Parton’s fans have been good this year, they might just wake up to one, or all, of these new books by and about Dolly wrapped up as holiday gifts.